The energy transition is arguably the most capital-intensive, complex, and urgent opportunity of our era. Despite how the term is commonly used, 'energy transition' doesn't refer just to a change in the mix of the energy generation technologies we rely on. Transition represents a wholesale shift of our infrastructure on multiple levels: from a power system based on steady load to one able to accommodate the electron-hungry, compounding growth of AI, cloud computing, and manufacturing; from a grid that uses generating assets in a binary, inflexible way to one that embraces technological advances that allow for bidirectional power flows, load matching, and lower capital expenditures; and from a generating base rooted in commoditized, legacy technologies to a more diverse base of assets selected for the ability to deliver electrons at the fastest speed to market and at the lowest cost. The energy transition of our time ties together imperatives of growth, flexibility, resilience, reliability, and long-term value creation. It also represents an unprecedented economic opportunity–and a daunting innovation challenge.

Throughout history, the development and adoption of technological innovation has fundamentally reshaped humanity's relationship with the world—consider the advent of antibiotics, steam engines, electrification, and computing. These transformations were not simple, they succeeded through complex interactions of multiple forms of capital, expertise, and policy. While entrepreneurs and innovators are remembered as the heroes of these revolutions, their success hinges on the support of a broader cast of characters, including public, private, and non-profit partners.

The advent of the internet serves as an important example of the economic opportunity and technological breakthroughs that can be delivered when resources are coordinated with intention. The internet today is synonymous with companies like Wikipedia, Google, and Amazon. The ability to exchange information over the internet–from knowledge to communication to transactions–represents trillions of dollars of economic value.

What you may not realize is that, at its outset, the development of the internet was largely funded by the U.S. government. In 1958, at the height of the Cold War, President Dwight D Eisenhower launched the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) to support innovators to build out network computing due to a need to develop a secure communication platform. This entity, which was the predecessor to the U.S. Department of Defense's D-ARPA, served as the catalyst for the first cross-network exchanges of information over what was originally called ARPANET. Innovations at non-profit academic institutions around the country, from Stanford to Dartmouth, built the infrastructure that enabled the internet's growth and widespread adoption, jump-starting a new engine of economic growth for the global economy.

Today, we find ourselves at a similar inflection point; we are operating within the Fourth Industrial Revolution, as defined by the World Economic Forum. This era is characterized by the convergence of advances in physical and digital technologies, unlocking unprecedented avenues for innovation. Technological advances alone, however, cannot drive progress; society needs to scale and adopt them.

To this end, the U.S. is endowed with three powerful forces with the potential to support a rapid transition to a stronger energy system. First, our financial ecosystem has evolved to become more sophisticated and capable of supporting rapid and transformative innovations. Second and third, the policy and philanthropic environments have more tools than ever before to accelerate such innovations. Private, public, and non-profit capital is inherently complementary and when coordinated can provide a bridge from start-up to scaled-up.

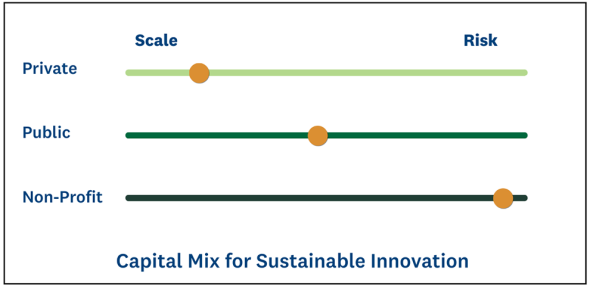

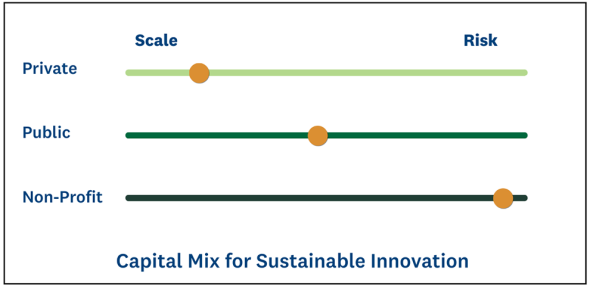

Non-profit capital, from philanthropic to academic, can take on almost unlimited risk in pursuing "moonshot" innovations; government capital trades off between providing innovations a platform to scale and de-risking private sector investment into sectors essential for economic growth; and private capital requires sufficiently attractive returns to justify investment and sufficiently mature business models to sustain cash flows but offers the promise of commercial scale operations and reach. Because private, public, and non-profit capital have inherently different risk tolerances and scale effects, they can enable innovation to progress rapidly when applied in coordination.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. We will discuss (1) Navigating the Financial Gauntlet: The "Valley of Death" in Energy Innovation, (2) Learning from the Past: Strategic Public Investment as a Catalyst, (3) Current Tools: Revitalizing Energy Supply Chains, (4) Catalytic Non-profit Capital, (5) A Case for Multi-Faceted Capital Coordination.

Scaling innovative early-stage startups into mature, sustainable organizations is a notoriously difficult endeavor. According to the Harvard Business Review, roughly 80% of startups fail to scale successfully, primarily due to deficiencies in operational capabilities and challenges with execution rather than inherent weaknesses in their core technologies. This "scaling gap" is particularly acute in the energy sector, where capital-intensive infrastructure and long development timelines add layers of complexity.

Energy startups face unique and daunting hurdles in the current funding landscape. Although private industry remains the largest single source of overall R&D funding in the U.S., contributing approximately 65% of all investments, overall investment in energy innovation continues to lag significantly behind other sectors.

By way of comparison, in 2019, investments in information technology outpaced energy innovation by a staggering factor of 70 to 1. This underinvestment is further highlighted by comparing the percentage of revenue that various industries dedicate to R&D: the software industry typically invests about 20% of revenue, healthcare around 10%, while the energy sector invests a mere 2%. This comparatively low level of investment is driven in part by concerns surrounding "stranded assets"—the risk that large infrastructure investments could become obsolete in a rapidly evolving innovation ecosystem. These factors combine to create a situation where American energy innovation remains chronically underfunded. Overcoming this challenge necessitates a multi-faceted strategy that leverages the unique strengths of both public and private capital.

Adding to these pressures is the infamous "valley of death," the perilous funding gap between initial proof of concept and widespread market adoption. While early-stage research often benefits from the support of non-profit and government grants, private-sector investment typically materializes only once a technology has demonstrated clear market readiness—and even then, often lags significantly.

The path from early funding to full-scale deployment, especially in hardware-intensive sectors like energy, is inherently risky and capital-intensive. Cost-effective energy manufacturing and deployment often occur at massive (gigawatt) scale and are deeply intertwined with complex supply chains. Consequently, energy technologies that require substantial manufacturing investments and/or lengthy qualification processes frequently encounter critical gaps in the existing funding landscape, leaving them stranded in the "no-man's-land" between growth equity investors and traditional infrastructure investors.

Although fund formation around energy hardware themes has seen increasing interest in recent years, driven by factors such as increasing load growth and growing concerns around supply chain security, the actual deployment of capital continues to lag significantly. These delays are driven by a combination of project-specific risks (related to project delivery), uncertainties regarding long-term margins, and high initial capital costs—particularly in areas like critical minerals processing / recycling, transformer manufacturing, and transmission development. These risks are often amplified for funds lacking deep expertise or a proven track record of successful energy investments, which today many U.S. funds still lack.

While the challenges facing energy innovation are significant, history provides valuable lessons and demonstrates the transformative power of strategic public investment. The U.S. boasts a long and successful history of public institutions proactively working alongside private industry to drive energy leadership. A prime example of this successful partnership is the introduction of the Intangible Drilling Costs (IDC) deduction in 1913. This forward-thinking policy allowed oil and gas developers to deduct a significant portion (60-80%) of their well-drilling costs in the first year, effectively mitigating the financial risks associated with developing new oil wells.

These deductions (and other current subsidies) continue to total approximately $20 billion USD of taxpayer dollars per year in the U.S. —despite the oil and gas industry having matured over the past century. This initial public investment played a crucial role in catalyzing private investment, mobilizing capital, and fueling a wave of petroleum-driven economic growth. Without such support, the North American oil and gas industry's development would have been markedly slower, and its current scale might never have been achieved.

While we can debate whether such subsidies should continue now that the technologies are deployed at scale, the key takeaway from the IDC example remains highly relevant today: Strategic public investment can serve as a powerful catalyst for de-risking emerging industries and unlocking private capital flows. In the same way that the IDC deduction fueled the initial growth of the oil and gas industry, targeted public investments can accelerate the development and deployment of critical clean energy technologies, ranging from advanced battery manufacturing to grid-scale energy storage solutions.

Despite steady support for fuel extraction and production, the U.S. pursued policies that led to chronic underinvestment in manufacturing of domestic energy hardware. This trend resulted in a significant outflow of manufacturing jobs to countries like China, Mexico, and parts of Asia. More recently, geopolitical disruptions and global pandemics have exposed the vulnerabilities created by these policies, highlighting how fragile global supply chains can threaten access to affordable and reliable energy—a resource vital to both our economic stability and our national security. Reshoring and strengthening domestic manufacturing capabilities has become a critical imperative for both economic and national security.

The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) represented a concerted effort to reverse these trends. Through these landmark pieces of legislation, the Department of Energy (DOE) catalyzed a substantial revival of American energy product manufacturing. A key component of this effort was the establishment of the Office of Manufacturing and Energy Supply Chains (MESC). A dedicated investment arm for the DOE, MESC was specifically created to address the "missing middle" of growth-stage capital willing to undertake giga-scale manufacturing risk in the energy sector.

MESC's mission is to complement the existing preferred debt financing instruments offered by the DOE's Loan Programs Office (LPO). Together, these two bodies enable the DOE to support commercial companies and projects that might not yet be mature enough to qualify for traditional debt financing. Informed by rigorous supply chain national security research, MESC makes strategic co-investments into large-scale energy manufacturing projects, with the explicit goal of increasing the availability of American-made energy products. In its first year alone, MESC demonstrated its impact by leveraging $12 billion in public funds to mobilize over $27 billion in private investment, a significant accomplishment that was made possible by lowering the risks and increasing the attractiveness of these projects. This initial wave of investments enabled the construction of more than 80 new manufacturing facilities across 31 states, revitalizing the nation's manufacturing sector and strengthening its overall economic resilience.

The BIL and the IRA offered agencies a range of financial tools—including grants, investment tax credits, and workforce skilling programs—to strategically deploy public capital in support of key energy projects. Loans, price floors, and even offtake guarantees were brought to the table to help companies bridge to scale. Through its strategic public investments, the U.S. spurred a near doubling of private-sector investment in manufacturing from approximately $60 billion in 2020 to nearly $120 billion by 2024. These numbers underscore the transformative potential of well-designed public investment in attracting private capital and strengthening critical domestic industries.

For these positive effects to continue, it is essential that these forms of public investment remain reliable. Policy inconsistency or abrupt changes that reduce or limit existing programs can quickly erode the private sector's trust in public funds, leading investors to discount the government and ultimately reduce their overall level of investment. On the other hand, changes that scale and innovate on public capital programs, such as the Pentagon's recent direct equity investment in rare earths player MP Materials through a reinterpretation of historic Defense Production Act authorities, can be catalytic in spurring private capital.

While the earliest forms of philanthropy in the U.S. were rooted in religious and community goals, the rise of American philanthropy has been inextricably tied to industrialization and economic growth. The foundations spurred by the fortunes of captains of industry, from Peabody to Carnegie to Rockefeller, drove much essential progress in American education and research.

Today, philanthropic forces are still very much rooted in industry, not just in their sources of funding, but also in the mechanisms that they employ to address societal challenges. Grants are just but one of the tools available, and increasingly the preferred tools mimic commercial vehicles and structures. For instance, the rise of impact investing spurred a culture of venture philanthropy. A prime example of this trend is the 2015 founding of Breakthrough Energy Ventures, an organization specifically designed to address the critical climate and energy challenges of our time. Building on this momentum, in 2019, the Rockefeller Foundation, Omidyar Network, and MacArthur Foundation joined forces to establish the Catalytic Capital Consortium (C3). Since then, numerous hybrid organizations, including Prime Coalition and Elemental Impact, have emerged, to develop mission-driven, patient capital systems to support energy innovation with a range of financial structures and instruments.

Moreover, philanthropic grants, along with loans offered on lenient terms, can serve as crucial bridges for promising ventures seeking to scale up their operations. De-risking mechanisms, such as subordinated capital, backstops, and first-loss arrangements—where public or philanthropic funds commit to absorbing initial losses—can incentivize greater participation from the private sector. Through the Climate Finance Partnership, the Hewlett Foundation and the Grantham Environmental Trust contributed seed funding to a half billion dollar blended finance investment fund to address energy transition challenges globally. When such strategic capital allocators are willing to shoulder risks that others are unable or unwilling to tolerate, they unlock access to additional private capital and foster a vibrant and thriving innovation ecosystem that generates cascading social and economic benefits. These multi-sector partnerships are vital for advancing our shared climate and economic goals across North America and beyond.

While overhauling the U.S. energy system to be as flexible, resilient, and scalable as our economy requires is certainly a challenge, we have never before had more tools to tackle it, especially through coordination across private, public, and non-profit sources of capital. These partnerships actively foster dynamic entrepreneurial ecosystems and pioneering approaches to financing high-impact ventures. While some may believe that the public sector should be limited to regulation and that the philanthropic sector should focus on traditional charitable activities, such a narrow view overlooks a crucial opportunity to support not only technological progress but also to drive its deployment to unlock economic growth.

We are already seeing some promising early examples of such collaboration among public, private, and philanthropic entities towards the objective of a stronger, modernized U.S. energy economy. For instance, in 2024, the Department of Energy established the Foundation for Energy Security and Innovation (FESI), an independent nonprofit aimed at facilitating partnerships between energy researchers, academic institutions, industry partners, and nonprofit and philanthropic organizations.

FESI is designed to accelerate the commercialization of promising energy technologies. It boasts a bipartisan genesis: conceived during the Obama administration and gaining momentum in the first Trump administration, the Foundation was eventually authorized and funded during the Biden administration under the CHIPS and Science Act., reflecting its consistent bipartisan support over more than a decade.

FESI is far from the first agency-related private foundation established to leverage philanthropy in support of key governmental and private sector objectives; it is actually the 13th such foundation. These foundations have been notably successful, raising an average of $67 for every dollar of federal contribution. This result demonstrates the effectiveness in advancing national objectives of strategically aligning private, public, and philanthropic resources.

The challenge of our time for the energy economy will require both technological innovation and at-scale deployment. Innovation thrives on sustained investment across the stages of growth, investment that is both willing to take risk and able to lend scale. To bridge across the valley of death, energy infrastructure and manufacturing must leverage a mix of nonprofit, public, and private capital. We know how to use these tools, with many historic and recent examples of their effectiveness. We also have built up some momentum, with technologies previously considered "alternative" now playing leading roles in new energy development. At the start of 2024, according to Rhodium Group and MIT, the U.S. for the first time in history outpaced China (and every other country in the world) on battery manufacturing investment. The question is where to go from here. Will the U.S. maintain its global leadership position in energy innovation, or will cutbacks blunt its push to retain and build on its competitive edge?

Giulia Siccardo '12 is a Distinguished Industry Fellow at the Irving Institute and Managing Director, Regional Leader for the U.S. with Quinbrook Infrastructure Partners.