Ali Bauer '25, a student in Assistant Professor of Anthropology Maron Greenleaf's Environmental Justice class and Dartmouth's Energy Justice Clinic, co-led by Dr. Greenleaf and Dr. Sarah Kelly, Geography Postdoctoral Researcher and Irving Institute Research Associate, connects a recent volunteer project with her in-the-classroom and EJ Clinic education.

On October 1, 2022, I volunteered with Cover Home Repair (COVER) to repair a mobile home in Woodstock, VT. When I first heard that I was repairing a home in Woodstock, I felt confused. When I think of Woodtsock, I think of a well-resourced town with beautiful tourist attractions. In reality, the home I helped on Riverbend Way resides in a low income, senior-dominated mobile home park — it sits adjacent to the Ottauquechee River, overtop a septic tank and leach field, hidden from the eyes of tourists and other Woodstock residents. "I would not have known where a lot of mobile home parks are — they tend to be tucked around," says COVER's Home Repair Co-Director and Dartmouth '82 Jay Mead. The location of "affordable housing" is often outside of cities and towns, and such geographic isolation often further disadvantages under-resourced communities.

The inaccessibility of public transportation is one example of a challenge caused by geographic isolation. Specifically, public transportation systems often do not reliably reach isolated communities in need. This means that individuals usually have to have a car (or a neighbor who has a car) and when that car fails, the consequence can be severe. Additionally, individuals have to pay for more gas than others due to their increased distance from grocery stores, doctors offices, schools, and so on. Barbara [note: A pseudonym is being used to protect the homeowner's privacy], who has been a Woodstock resident for around 70 years, explains that when public transportation is offered to Riverbend Way twice a month, it costs $20. In response to the price, Barbara says, "I can't do that."

My time volunteering revealed to me that inequities in housing lead to additional burdens like high energy costs and climate change-related risks of flooding and hurricane damage. The fragility of mobile homes looks different depending on the homeowner. For Barbara, she observes a "soft spot" in her house. The "soft spot" is temporarily covered by carpet to reduce her risk of falling through her bathroom into the crawlspace. She cannot afford to hire someone for help, so she hopes her sons will fix the floor soon.

Despite the risks associated with living in a mobile home not equipped for the New England climate, COVER employee Jay says that Riverbend Way is important because "there are very few affordable housing options in Woodstock." Jay says that used mobile homes typically sell for $5,000-$10,000, while new ones go for around $60,000. Jay adds that most homes in Riverbend Way are "southern buildings, not heavy duty, made to be light and mobile," and, "indigenous architecture [which is seen in the popular tourist communities in Woodstock] is slowly dying because only the wealthy can keep it up." Mobile homes are often the only means of access to homeownership for persons of limited financial means. Mobile homes have a low entry barrier (low cost) but over the life of the home, tend to be more expensive to maintain and heat compared to a traditional wood-framed home.

The lack of insulation in many mobile homes — particularly in older mobile homes — result in relatively high energy costs; this is actually what brought me to collaborate with COVER in the first place. As a current Dartmouth student enrolled in Assistant Professor of Anthropology Maron Greenleaf's Environmental Justice course and active in Dartmouth's Energy Justice Clinic, co-led by Dr. Greenleaf and Geography Postdoctoral Researcher and Irving Institute Research Associate Sarah Kelly I study energy insecurity and energy justice in the Upper Valley. In addition to learning through case studies in the classroom, my workday confirmed that the materials that construct many mobile homes create structures that are "not properly insulated," which Jay explains "dumps energy out" of homes. As a result, mobile homeowners have a disproportionately higher cost burden for heating and cooling. Jay finds that "people spend so much money on energy for such a small tank." Barbara agrees, saying that she spends "$900 a winter after subsidies" on heating alone. On Social Security, she is provided one tank of fuel to heat her home, but she needs three to get her through the winter comfortably.

In addition to the current struggles of its mobile home owners, Riverbend Way has been disproportionately affected by climate-change-related disasters. In 2011, Tropical Storm Irene flooded Riverbend Way with water levels "five feet above ground," according to Barbara. The high-risk location of Riverbend Way is not atypical for its demographic; Jay explains, "poor people and farmers typically live low in river valleys." As a result, Irene caused impoverished and working-class individuals the most damage in Woodstock, VT. Specifically, farmers lost their land and livelihood, and the hurricane destroyed most — if not all — possessions of impoverished folks who do not have the funds to replace what they lost. Barbara further explains that, "most of the trailers on the left side [of Riverbend Way] were ruined," including her own home. People, including Barbara, eventually returned to the area with hurricane relief checks from the government. Unfortunately, due to the unchanged proximity of Riverbend Way to the Ottauquechee River, Riverbend Way and its population is vulnerable to another disaster.

Another critical issue is that many mobile homeowners do not own the land that they live on, which places a whole other economic stress on them associated with added risks and costs. "Woodstock has changed." Barbara says the price of living in Woodstock has increased incredibly, even on Riverbend Way. Barbara said she used to pay the mobile home park, owned by a private group, $75 a month, until 2003. Now, she pays $462 a month to Housing Foundation Inc. for the same spot of land.

Barbara describes Woodstock as being "overrun," not just financially, but also culturally. She says that her family did not have much money, but when she was younger, people knew each other and cared about each other. She recalls a friendly culture throughout Woodstock in which people introduced themselves and casually talked on the streets of town; now, she feels that people are always stressed and in a rush.

Barbara explains that she imagines that a large shift in Woodstock occurred when more people from New York moved to Woodstock. Barbara adds that Riverbend Way is now composed mainly of senior citizens, and it used to be home families to dairy farmers or loggers. Barbara explains, "people don't say 'hi' to each other anymore on the street" and says that community involvement is almost nonexistent. Barbara attributes lack of community involvement to decreased need for collaboration because "things can just be paid for now." She also explains that she only drives "out of necessity." When asked if it was due to gas prices, she says, "no." Barbara further explains that she feels unsafe driving nowadays because "people are always on their phones."

Barbara says she feels most unhappy about the changes in her community because "it makes life so much harder for the people who've been living here for so long." She thinks that because the people who took over Woodstock have money, they feel a sense of superiority over older, less affluent residents. Barbara describes feeling helpless in a changing community, where she feels money represents power. Barbara shares that she is a consistent voter and a "loyal Democrat." Still, she feels that she is underrepresented politically and socially within the largely affluent Woodstock community. Jay reinforces Barbara's feelings of frustration with living in poverty in America, saying that the wealth gap and housing crisis are systemic issues.

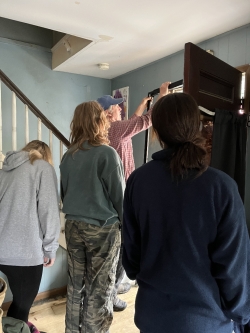

I really appreciated my experience with COVER because employees and volunteers encouraged questions and engaged with Barbara. COVER workdays are led by trained, professional employees with help from community volunteers. According to their website, "Cover Home Repair has been bringing together volunteers and homeowners to complete urgently needed repair projects for low-income homes in the greater Upper Valley," and keeping the community "warm, safe, and dry," since 1998. To qualify for help from COVER, a home must demonstrate an urgent need for health and safety, be located within 45 minutes of White River Junction, and have a total household income less than 60% of the area median income. In addition, COVER invites homeowners and their families to participate in the home repair projects as equal partners. Participation can take the form of making lunch or eating lunch together, and also working alongside volunteers if they are able to.

Other projects that COVER works on include, "urgent home repairs affecting health and safety, weatherization and energy conservation services, fall prevention (trip hazards), and repurposing furniture, appliances, tools, and building materials" (Home Repair). Jay explains that COVER is primarily funded through a mix of foundation grants, individual donations, and proceeds from a second-hand thrift store. Additionally, COVER receives modest funding from the Vermont Center for Independent Living and Granite State Independent Living for some accessibility ramps to help homeowners enter and leave their homes safely. Homeowners do not need to pay for services, however, they are encouraged to make a contribution towards material costs if they can do so. Often this means a homeowner contribution of $50 to $200.

Over the last 24 years, COVER has been helping homeowners continue to live in their homes. Over half of its homeowners live in mobile homes, many of which are energy-inefficient with high heating and cooling costs. COVER recognizes that an inefficient home will quickly become unaffordable to a person of limited financial means.

COVER helped Barbara by insulating her crawlspace to reduce energy costs. The process is not perfect, though; Jay warns, "don't let perfect be the enemy of the good: foam insulation panels are not ideal environmentally, but saving oil in the long run works well for what it is." He describes the work COVER does as a "band-aid," because it temporarily helps individuals instead of directly addressing systemic injustices within America's housing system. Jay explains, "these places [mobile home parks] should not exist environmentally, but people need mobile housing — this is a short term solution." The existence and repair of fragile mobile homes represent a placeholder while people search for better ways to better accommodate disadvantaged communities.

The financial, social, and environmental costs and benefits of housing solutions limit what is realistic and what is not. Jay says that "not until you build more housing and make it affordable" will the housing crisis be fixed. Ultimately, energy security is influenced by privilege, and only a systemic reboot in which safe, functional housing is made affordable and accessible will energy justice be served.

Ali Bauer (she/her) is a Dartmouth '25 originally from the Philadelphia area now living in rural Vermont. She is studying Environmental Studies and Geography and started her work with the Energy Justice Clinic in the beginning of fall 2022. Ali also takes part in undergraduate research with the Earth Sciences Department, hosts a podcast — she did a recent episode about her work with COVER and the Energy Justice Clinic — works as a UGA and tour guide on campus, and spends time outdoors.